FUNDACIÓN LÁZARO GALDIANO, MADRID. 20 OCTUBRE 2008 – 5 DE ENERO 2009

El haya centenaria del jardín de la Fundación Lázaro Galdiano va a ser talada. Se trata de un árbol de gran porte que tiene:

-importancia botánica en Madrid, pues hay muy pocas hayas en la ciudad, y menos de esta edad. Se conserva solamente otra de la misma envergadura en el Jardín Botánico.

-importancia histórica para la Fundación, pues fue plantado por José Lázaro Galdiano en un intento de acercar a su casa los bosques navarros.

-importancia sentimental para todos aquellos que han tenido un contacto continuado con el jardín, sean trabajadores o visitantes.

Visión-fantasma

Visión-fantasma

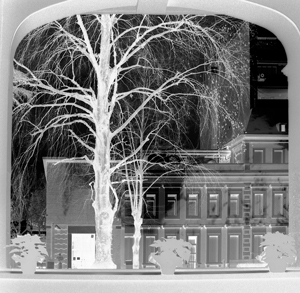

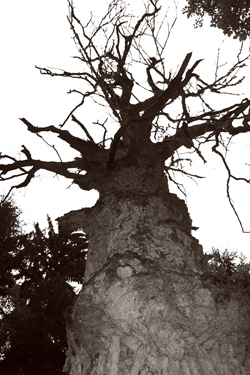

Desde el interior del edificio principal de la Fundación, el haya se ve hoy sobre todo a través del gran ventanal de la tienda. Quería fijar en él la imagen. Para ello, he trasladado al vidrio, de forma sutil, esa vista desde el interior. No el árbol con toda su copa, sino el fragmento del tronco y de las ramas que se ve ahora desde aproximadamente el centro de esa estancia.

Sombra luminosa

En el atardecer se empezará a dibujar sobre la fachada del edificio principal que da al jardín, centrada en el torreón, la sombra del haya ausente. Para ello se ha instalado un potente foco con la silueta del árbol. Se ve no la sombra sino el negativo de la sombra, es decir, una figura de luz.

Dos libros en la Biblioteca del Bosque

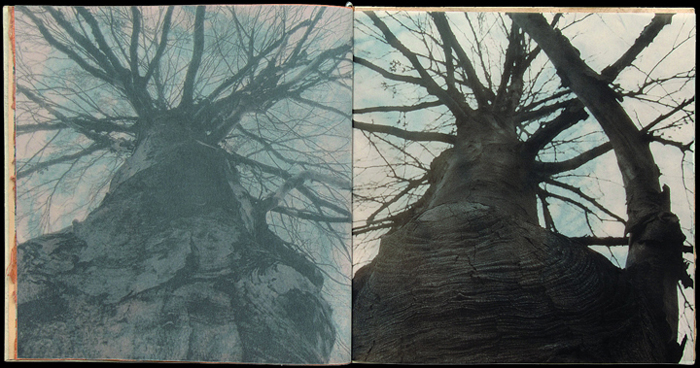

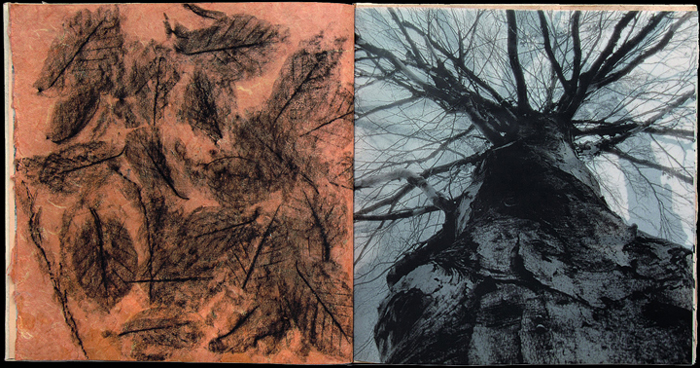

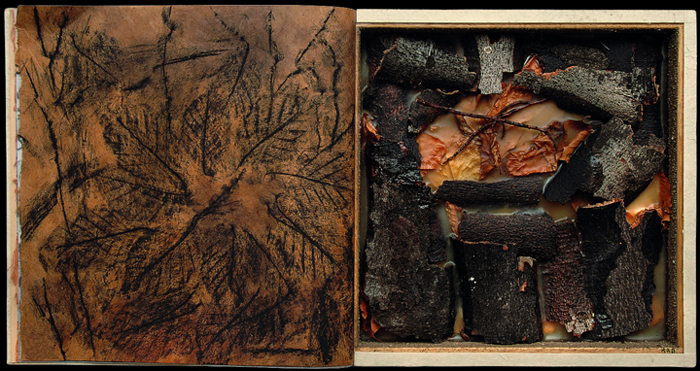

Libro nº 1049

LAS ÚLTIMAS HOJAS DEL HAYA LAZARUS

31.1.2008 – 300 x 300 x 40 mm

8 páginas de papel vegetal con estampaciones fotográficas y papel de fibras con frotaciones de hojas y ramas del haya

Caja con cortezas, hojas y ramas caídas del haya centenaria (Fagus Sylvatica purpurea) del jardín de la Fundación Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid, sobre tierra y cera

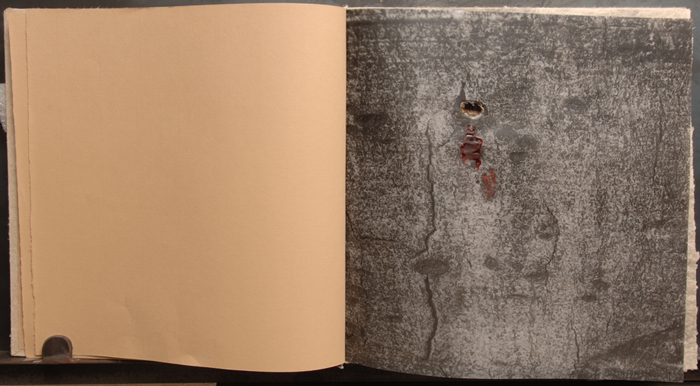

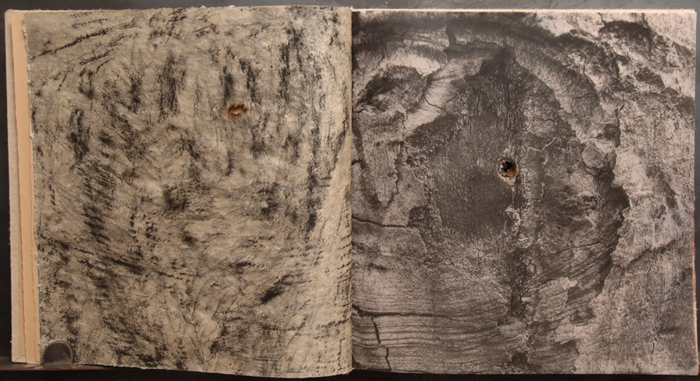

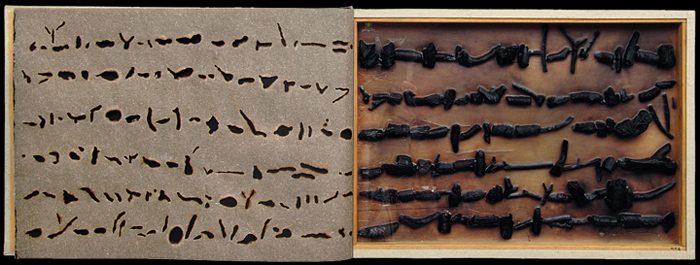

Libro nº 1064

HAYA INTERIOR

16.10.2008. 300 x 300 x 55 mm

10 páginas de papel verjurado, papel vegetal con impresiones fotográficas y papel hecho a mano de Nepal y México con frotaciones del tronco del haya de la Fundación Lázaro Galdiano, perforación de fuego y sangre

Caja con cortezas del haya y muestra de su madera interior extraída con sonda forestal, sobre resina

Exposición sobre el poder de los árboles caídos

Selección de la Biblioteca del Bosque con libros que contienen elementos y materiales de árboles históricos y legendarios, heridos o desaparecidos. Constituye una senda a través de la noche de los árboles antiguos o caídos que he conocido y he vivido, en la sala de exposiciones del Museo.

Además, se plantará un haya joven en sustitución de la antigua.

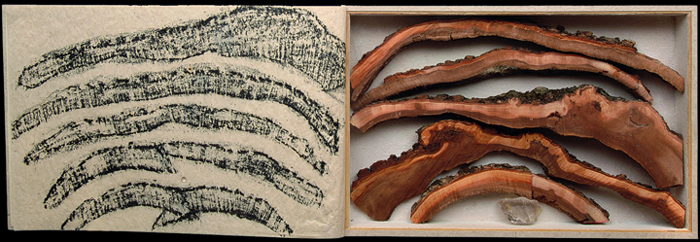

Libro nº 776

RASCAFRÍA. ULMUS MINOR LUX

31.3.2000 – 420 x 640 x60 mm

4 páginas de papel reciclado y papel de Nepal con frotacciones de cortezas de olmo

Caja con secciones del tronco de la olma de Rascafría, caída por el peso de la nieve, y cristal de roca sobre polvo de mármol

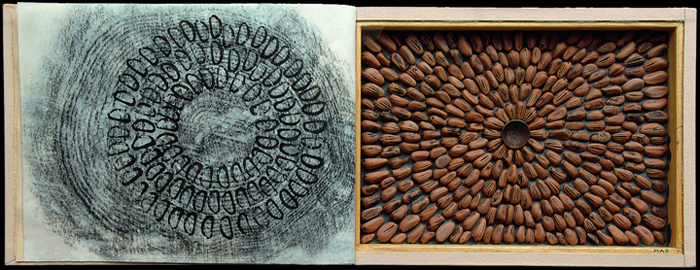

Libro nº 790

LA SALVACIÓN DEL PINAR DEL REY I

1.12.2000 – 205 x 280 x 32 mm

6 páginas de papel verjurado y papel de croquis con frotaciones de anillos de crecimiento y huellas de piñones

Caja con 293 piñones de pino piñonero (Pinus pinaster) del Pinar del Rey, Madrid, y cuenco de hierro sobre carburo de silicio

Libro nº 909

DRIADAS

29.3.2004 – 170 x 290 x 30 mm

6 páginas de papel verjurado y papel vegetal milimetrado con estampaciones fotográficas

Caja con raíces-tea de pino piñonero caído en el Jardín de El Capricho, Madrid, y 5 gotas de ámbar de Lituania

Libro nº 916

PICÓN DE ENCINAS

26.5.2004 – 295 x 415 x 30 mm

4 páginas de papel verjurado y papel mexicano de pochote hecho a mano con quemaduras

Caja con picón (encina carbonizada) del Valle de Alcudia sobre parafina

Libro nº 924

ÁRBOL DE GERNIKA

20.7.2004 – 165 x 230 x 32 mm

6 páginas de papel vegetal rojo y papel pizarra quemado

Caja con cinco ramas tronchadas por el viento del roble de Gernika, cera y carburo de silicio

Libro nº 938

LOS ROBLES REALES

28.11.2004 – 300 x 420 x 65 mm

4 páginas de papel verjurado y papel de Nepal hecho con fibras de morera, cubierto de serrín de cortezas de pino, con frotaciones al óleo sobre cortezas de robles y quemaduras

Caja con cortezas de 450 años de antigüedad de la senda de los Robles Reales en Bialowieza, Polonia, serrín de cortezas y bellota

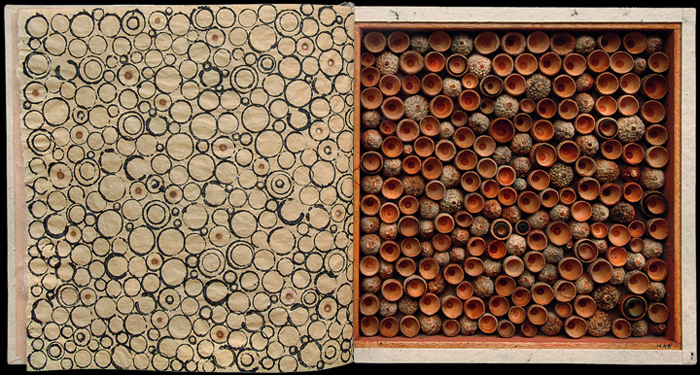

Libro nº 954

CÚPULAS SINFÓNICAS DE ENCINAS

4.4.2005 – 250 x 250 x 33 mm

Caja con 216 cúpulas de encinas de La Ardosa, Valle de Alcudia, arena del crematorio de Mari Karnika a orillas del Ganges, Veranesi y tierra de Jaisalmen, desierto del Thar, India

Libro nº 965

PALO DE TRES COSTILLAS

15.7.2005 – 185 x 93 x 42 mm

4 páginas de papel de grabado con gofrados de acículas y grafito

Caja con palo de tres costillas (Serjania mexicana) Museo de Tepoztlán, exconvento de La Natividad, Morelos, sobre carbón de silicio, Cuenca

Libro nº 971

SEÑOR DE BERTIZ

11.9.2005 – 205 x 285 x 60 mm

4 páginas de papel vegetal con estampaciones fotográficas del roble caído y del roble erguido

Caja con cortezas y serrín sacadas del hueco interior de un roble caído en el jardín secreto de Bertiz, Navarra, y corteza del gran cedro de Bertiz

Libro nº 998

LO QUE SIENTEN LOS PLÁTANOS DEL PASEO DEL PRADO

22.5.2006 – 140 x 205 x 32 mm

6 páginas de papel verjurado, papel de pochote y papel de fibras vegetales con trazos de grafito y tinta china

Caja con escama de corteza contaminada de uno de los plátanos del Paseo del Prado, Madrid, y vainas papiriformes o caliptras sobre cera gris

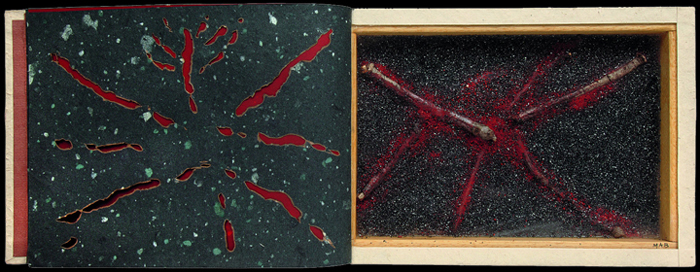

Libro nº 1000

TROMBIOSIS

23.6.2006 – 200 x 285 x 60 mm

10 páginas de papel vegetal con estampaciones fotográficas y decoloraciones

Caja con nudo de roble antiguo de Quintanar de la Sierra, junto a la necrópolis de Cuyacabras, Burgos, señal de la trombosis que sufrí posteriormente en el brazo derecho, cera roja y sangre

Libro nº 1024

LAS RAÍCES DE LINNEO

28.2.2007. 200 x x285 x 62 mm

8 páginas de papel verjurado y papel vegetal con estampaciones fotográficas en color

Caja con gálbulos y raíces de la arizónica (Cupressus arizonica) caída la madrugada del 9 de febrero por el viento en la plaza de Linneo, Madrid, hongos xilógrafos del almez seco en el Jardín Botánico de Madrid, fluorita y parafina

Libro nº 1027

ÁRBOL INTERIOR SAQQARA

4.4.2007 – 102 x 102 x 28 mm

4 páginas de papel verjurado y papel vegetal con estampación fotográfica

Caja con tres astillas de una viga de madera que sobresalía desde el inerior de la cara oeste de la pirámide escalonada de Saqqara, sobre algodón y arena de Egipto

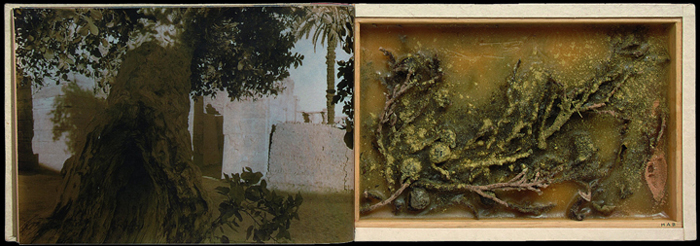

Libro nº 1035

SICOMORO SEJEMET

9.5.2007 – 190 x 290 x 35 mm

6 páginas de papel verjurado y papel vegetal con estampaciones forográficas

Caja con higos y ramas de sicomoro (Ficus sycomorus) deltemplo de Karnak, henna, cera y arena del desierto egipcio

Libro nº 1047

CIPRÉS DE SAN JUAN DE LA CRUZ

15.11.2007 – 150 x 230 x 33 mm

8 páginas de papel verjurado, papel hecho a mano con fibras de musgo y papel vegetal con estampaciones fotográficas

Caja con astilla del medio cipres-enebro plantado por San Juan de la Cruz en Segovia y ramas de su renuevo sobre cera violeta

MIGUEL ÁNGEL BLANCO

El árbol es uno de los más firmes ejes de la vida material y espiritual de numerosas culturas, con una historia inmemorial. Hoy continúa siendo una gran fuente de conocimiento, caudalosa para quienes comprenden su valor y sienten su energía. Mi Biblioteca del Bosque, iniciada en 1985 y compuesta en la actualidad por 1055 libros-caja, se ha construido en torno a ese eje ―aunque haya dado cabida a otras muchas formas orgánicas e inorgánicas―, siempre a partir de experiencias personales. La muerte del haya roja (Fagus sylvatica var. purpurea) en el Jardín Florido de la Fundación Lázaro Galdiano ha dado pie a esta exposición que revisa mi relación con individuos arbóreos de particular relevancia, por su antigüedad, su carácter legendario, su protagonismo en mi entorno vital y artístico. Mi devoción hacia ellos. Son árboles vividos y ensoñados cuya existencia es inmortalizada en mi Biblioteca y que, juntos, constituyen un bosque de presencias imponentes. El homenaje, la protección y la renovación han sido las formas de diálogo con ellos más frecuentes.

Los yacimientos arqueológicos, los museos de historia natural y las especies prehistóricas que se han perpetuado hasta hoy dan testimonio de la sabiduría con la que el árbol ha hecho frente a las adversidades geológicas y climáticas. Unas especies son más longevas que otras, pero siempre han existido ejemplares con particular resistencia al tiempo, venerados por su antigüedad. Cuando su vida se extingue por causas naturales no nos queda más que admitir la justicia de los ciclos vitales y admirar el poder que conserva el árbol caído. Pero el árbol, más allá de su explotación sostenible para la obtención de madera, está bajo la amenaza del ser humano. La excelencia de la naturaleza nos ha dado los árboles y nuestra obligación es preservarlos. En vez de ello, vemos cómo grandes extensiones forestales son mermadas y, a nivel más local, cómo se trata con desprecio a los árboles en las calles y en los jardines. Por razones diversas, entre otras las obras de rehabilitación del palacio y una mala actuación “paisajística” que cortó parte de sus raíces secundarias, el haya roja del Jardín Florido, que tenía más de cien años, se secó. La consternación del personal de la Fundación Lázaro Galdiano y de todos aquellos que conocían y amaban a este magnífico ejemplar fue muy grande. Se estudiaron las posibilidades de salvarlo y se concluyó que no eran viables. La Dirección General de Bellas Artes del Ministerio de Cultura quiso entonces, en colaboración con la Fundación, encargarme un proyecto artístico para hacer perdurar de alguna manera la presencia del árbol. Lo primero que hice fue tener una audiencia con el haya, que tuvo lugar el 7 de diciembre de 2007, con el fin de comunicar con su poder, sentirlo e interpretarlo. También visité el otro haya centenaria existente en Madrid, que se encuentra, esplendorosa, en el Real Jardín Botánico. Y realicé una expedición al Hayedo de Montejo, helado. Tras este cónclave de las hayas, el código comunicativo que elegimos fue el del húmedo silencio, el de la levedad y la transparencia. El proyecto, el renacer del haya, será sombra luminosa y hielo, luz y cristal escarchado.

Al igual que el árbol nunca puede ser percibido desde un único punto de vista, el memorial del haya debía tener varias perspectivas, expresadas en diferentes medios, visibles desde diferentes ubicaciones y con distintas condiciones lumínicas, diurnas y nocturnas. Son, por tanto, tres intervenciones en el jardín las que evocan sutilmente la presencia ya fantasmal del árbol. La primera consiste en la proyección de la silueta del haya seca sobre el torreón del museo. Al atardecer se empieza a dibujar sobre la fachada del edificio que da al jardín, centrada en el torreón, la sombra luminosa del árbol ausente. Se ha instalado un potente foco que muestra no la sombra sino el negativo de la sombra, es decir, una figura de luz. La segunda intervención ha fijado, a través del grabado al ácido en el gran ventanal de la tienda, la parte de la imagen del árbol que se veía desde el interior y a través de él ―aproximadamente desde el centro de esa estancia―. Esta forma de trabajo enlaza con la destacada colección de objetos de vidrio y cristal que atesora el museo. La tercera, de la que soy sólo promotor y testigo, cierra el ciclo vital con la plantación de una nueva haya roja traída, como la que murió, de Navarra, de donde procedía también Lázaro Galdiano.

El proyecto se completa con la realización de dos libros-caja de la Biblioteca del Bosque con materiales del haya: uno con sus últimas hojas y otro con su madera interior. Y con la exposición Árbol caído en la sala de exposiciones de la Fundación Lázaro Galdiano, una senda a través de la noche de los árboles antiguos o caídos que he conocido y he vivido. Libros-caja que contienen partículas de estos árboles y sus experiencias. Su viaje al más allá.

He querido dividir la exposición en diferentes apartados o secciones, reuniendo árboles clasificados en distintas categorías.

ÁRBOL DE PIEDRA

Son los fascinantes árboles fósiles, caídos y eternizados por la petrificación. En abril de 2007 se encontró el árbol más antiguo conocido hasta la fecha, con 385 millones de años, que vivió en unas fechas en que aún no habían aparecido sobre la Tierra ni los dinosaurios ni, por supuesto, el hombre. Sus únicos compañeros eran los artrópodos. Es un ejemplar de Wattieza cladoxylopsid del Devónico, un tipo de helecho arborescente hallado en el condado de Schoharie, en el estado de Nueva York. Tiene casi nueve metros de altura y, de manera excepcional, conserva las ramas y las raíces; se mantenía en pie cuando fue cubierto por sedimentos y posteriormente se fosilizó. Igualmente impresionantes son los bosques petrificados del noreste de la provincia de Santa Cruz, en la Patagonia argentina, más jovenes ―unos 130 millones de años― y por tanto con árboles más evolucionados, del tipo de la araucaria. A principios del Cretácico, las erupciones volcánicas enterraron esos bosques en cenizas, por lo que algunos troncos quedaron en pie y forman hoy grandes conjuntos de fósiles.

Son los fascinantes árboles fósiles, caídos y eternizados por la petrificación. En abril de 2007 se encontró el árbol más antiguo conocido hasta la fecha, con 385 millones de años, que vivió en unas fechas en que aún no habían aparecido sobre la Tierra ni los dinosaurios ni, por supuesto, el hombre. Sus únicos compañeros eran los artrópodos. Es un ejemplar de Wattieza cladoxylopsid del Devónico, un tipo de helecho arborescente hallado en el condado de Schoharie, en el estado de Nueva York. Tiene casi nueve metros de altura y, de manera excepcional, conserva las ramas y las raíces; se mantenía en pie cuando fue cubierto por sedimentos y posteriormente se fosilizó. Igualmente impresionantes son los bosques petrificados del noreste de la provincia de Santa Cruz, en la Patagonia argentina, más jovenes ―unos 130 millones de años― y por tanto con árboles más evolucionados, del tipo de la araucaria. A principios del Cretácico, las erupciones volcánicas enterraron esos bosques en cenizas, por lo que algunos troncos quedaron en pie y forman hoy grandes conjuntos de fósiles.

En España tenemos un yacimiento de árboles fósiles en el entorno del pueblo de Hacinas, en la Sierra de la Demanda, con la misma antigüedad que los de la Patagonia. En esos tiempos había en Burgos un caluroso y húmedo clima tropical que permitió el desarrollo de una espesa selva en la que crecía una variedad de conífera de la familia de las podocarpáceas, que podía alcanzar los 80 metros de altura.

A lo largo de los años me he interesado por los xilópalos, fragmentos de troncos o ramas fósiles que atrapan la edad infinita de los árboles, y he reunido una pequeña colección. Los he utilizado en algunos libros, como el nº 312, Astillas de un bosque petrificado en Albacete, o el nº 779, Tremor en el castaño de El Tiemblo, en el que incluí dos rodajas de xilópalo procedentes de Madagascar, con una antigüedad de 80 millones de años, junto a unas castañas del centenario “El abuelo”.

ÁRBOLES MÍSTICOS, LEGENDARIOS Y PROFÉTICOS

El árbol es un símbolo universal. Venero de sabiduría, tiene un papel destacado en ceremonias de muchas culturas y religiones, y es personaje de numerosas narraciones míticas y leyendas. Está implicado en diversas cosmogonías, en historias de fundaciones de ciudades, de revelaciones, de epopeyas históricas o imaginarias. Árboles que tuvieron o no una existencia física pero que viven en la memoria; ejemplos de sorprendente perennidad, por su asociación a restos arqueológicos o por el cuidado que muchas generaciones han puesto para hacer vivir los renuevos de esos árboles venerables.

Uno de los más célebres es el pipal o árbol de Bodhi bajo el que Siddhartha Gautama se convirtió en Buda tras alcanzar la iluminación, en Bodhgaya, estado de Bihar, India. En el lugar que ocupó vive un descendiente suyo con seis de cuyas hojas, reducidas a sus nervaciones, realicé el libro nº 740, Ficus religiosa, nombre científico de ese tipo de higuera. La tradición dice que, después de la iluminación, durante una semana Buda siguió sentado donde estaba, meditando; la semana siguiente hizo lo mismo caminando y la tercera la dedicó a contemplar el pipal. Sobrevivió durante siglos y, además, tiene numerosos hijos en India y otros países budistas: es especialmente reverenciado el que florece en el monasterio Mahavihara de Anuradhapura, en Sri Lanka.

También en países desérticos, como Egipto, han desempeñado los árboles un papel de importancia capital. Hatshepsut quiso justificar la usurpación que la llevó al poder y ganarse el favor de los sacerdotes de Amón ofreciéndoles el olivano, o incienso en resina, sustancia ritual imprescindible para el culto. Organizó una gran expedición marítima al Punt para llevar a Egipto el árbol del incienso (Boswellia sacra), enviando allí cinco grandes navíos hechos con espléndidos troncos de cedro del Líbano con mástiles de nueve metros de altura. Ella consideró este viaje como la culminación de su reinado, y así lo hizo saber en los exquisitos relieves de su templo funerario en Deir el-Bahari, de gran interés etnográfico y botánico. El templo estuvo rodeado de estanques y jardines, y en el recinto quedan tocones de los viejos árboles que plantó la reina. De esos tocones extraje unas astillas conservadas en el libro nº 1028, El árbol del incienso de Hatshepsut.

Los enclaves religiosos no sólo incluyeron árboles en los jardines, sino que alcanzaron sus formas arquitectónicas canónicas a partir de la elaboración de las construcciones vegetales en las que se realizaron las ceremonias más ancestrales. Así, en el complejo funerario de Zoser en Saqqara, el arquitecto Imhotep imitó los tallos de palmera o de papiro en las columnas nervadas. De la fachada oriental de la pirámide escalonada sobresalen dos viejos troncos de madera hacia los que trepé por la piedra ardiente para obtener tres astillas guardadas en la caja del libro nº 1027, Árbol interior Saqqara.

A Karnak se llevaron los árboles del incienso de Hatsepshut, pero no son los únicos que crecieron y crecen en el recinto más sagrado de Egipto. En su extremo septentrional, fuera del trasiego de visitantes, una de las tres capillas del templo de Ptah está dedicada a la diosa Hathor, que habita allí en forma de una de sus manifestaciones, la leona solar Sekhemet; es una impresionante estatua de granito negro sumida en la oscuridad e iluminada cenitalmente por la luz del ocaso de Tebas. A la puerta de ese templo crece un sicomoro, que fue el árbol asociado a Hathor: uno de sus títulos era el de “Señora del sicomoro”. No sería raro que ese árbol, del que tomé los rezumantes higos y unas ramitas que se ven el libro nº 1035,Sicomoro Sejemet, fuera descendiente de los que en tiempos faraónicos debieron rodear la construcción. El sicomoro, por otra parte, fue una especie muy valorada por los egipcios porque con su madera se fabricaban los mejores sarcófagos, y confería así a los muertos vida eterna. El Libro de los Muertos lo expresa así: “He abrazado el sicomoro y el sicomoro me ha protegido; las puertas de la Duat me han sido abiertas”. Además, sus fibras se utilizaron para tejer los cordones de los que colgaban los amuletos de vivos y muertos.

La mística y el árbol se vinculan a menudo. En lo más alto del monasterio de los Carmelitas Descalzos en Segovia se yergue el esqueleto del ciprés―otro árbol funerario― que allí plantó, en el siglo XVI, San Juan de la Cruz. Fragmentos de su madera seca, recogidos a la luz crepuscular reflejada por el Eresma, agua encendida, y de los renuevos que han nacido de sus raíces, se reúnen en el libro nº 1047, Ciprés de San Juan de la Cruz. San Juan plantó otro ciprés, éste vivo, en el Carmen de los Mártires de Granada, a cuya sombra, dicen, escribió La noche oscura del alma. Es curiosa la indefinición botánica de los árboles plantados por el santo, pues al de Granada se le ha conocido tradicionalmente como “el cedro de San Juan” y el de Segovia, según el vigilante de la capilla alta, sería un ciprés-enebro (?) de madera incorruptible.

La mística y el árbol se vinculan a menudo. En lo más alto del monasterio de los Carmelitas Descalzos en Segovia se yergue el esqueleto del ciprés―otro árbol funerario― que allí plantó, en el siglo XVI, San Juan de la Cruz. Fragmentos de su madera seca, recogidos a la luz crepuscular reflejada por el Eresma, agua encendida, y de los renuevos que han nacido de sus raíces, se reúnen en el libro nº 1047, Ciprés de San Juan de la Cruz. San Juan plantó otro ciprés, éste vivo, en el Carmen de los Mártires de Granada, a cuya sombra, dicen, escribió La noche oscura del alma. Es curiosa la indefinición botánica de los árboles plantados por el santo, pues al de Granada se le ha conocido tradicionalmente como “el cedro de San Juan” y el de Segovia, según el vigilante de la capilla alta, sería un ciprés-enebro (?) de madera incorruptible.

El ciprés es símbolo de longevidad, y en la China antigua se consumían sus semillas para dotarse de ella; también se aseguraba que si se frotaban los talones con su resina, se podría caminar sobre el mar. El ciprés más antiguo de la ciudad de Granada, con 600 años de edad y ya seco, se encuentra en un patio del Generalife al que da nombre: es el “ciprés de la sultana”, paradigma de una categoría de árboles que propician los encuentros furtivos. Bajo éste, dice la leyenda, la mujer de Boabdil tenía encuentros con un abencerraje; la venganza del rey contra todos los varones de la familia del traidor dio nombre a la una de las más bellas de la Alhambra. El ciprés, según la leyenda, fue fulminado por un rayo, y es recordado en el libro nº 1052.

También van de la mano el árbol y el chamanismo. En el libro nº 392, Raíz del nagual, que recoge en su caja fragmentos de un anciano nogal abatido por el viento, se recuerda al espíritu animal, vehículo de los dioses, que da poder a los chamanes y que, en la tradición tolteca, es el doble proyectado que cada ser posee desde su nacimiento, encargado de protegerlo y guiarlo. El nagualismo dice que los árboles están más cercanos al hombre que las hormigas. Árboles y hombres comparten emanaciones. Antiguos videntes desarrollaron técnicas de brujería para atrapar la conciencia de los árboles, usándolos como guías para bajar a los niveles más profundos. El nogal es mi nagual. En la rama que hay en el libro perforé una forma trapezoidal similar a las que he visto en representaciones antiguas de los chamanes mexicanos.

Conseguí en la puerta principal del mercado de Sonora, en Ciudad de México, que está especializado en plantas curativas y materiales para la magia, unos extraños fragmentos de madera con vetas oscuras que me vendieron como “árbol de la víbora”, remedio para infecciones y hongos. He clasificado el libro que hice con ellos, el 794, entre los árboles míticos porque no he conseguido identificar esa especie sanadora o mágica. Sólo encontré un estudio sobre curanderos de Veracruz en el que se habla de un “árbol de la víbora” descrito como Erythrina americana. Por lo que he sabido, no se corresponde con los fragmentos que tengo. Involuntariamente, he hecho compartir el misterio con quienes han visto la reproducción de mi libro en algún catálogo, y he recibido algunas consultas al respecto que no he podido contestar.

En México, los árboles están en el origen de fundaciones de ciudades. Tenochtitlán (hoy Ciudad de México) se ubicó en el entorno señalado por la legendaria águila que, tras cientos de años de peregrinar, se posó en la cima de un nopal para devorar a una serpiente en el año 1325. A ese acontecimiento dediqué el libro nº 799, La gran Tenochtitlán, con fragmentos de raíz de nopal de Zacatecas (no incluido en la exposición). El nopal no es en propiedad un árbol, sino una cactácea,―aunque los ejemplares añosos pierden sus hojas inferiores y crecen sobre un tallo leñoso― y su capacidad de renovación lo convierte en símbolo de inmortalidad. Sí lo es el gran mesquite (o mezquite, del nahuatl mizquitl) que crece junto al Templo de Santa María Magdalena en Tequisquiapán. La historia revela que bajo él se celebró la misa de fundación de la ciudad en 1551; pero la población existía antes, y circula la leyenda, seguramente inspirada en la de la antigua Ciudad de México, de que otro águila fundadora se posó en el mesquite en tiempos prehispánicos; las vainas de sus semillas están en el libro nº 921, Mesquite, árbol fundador de Tequisquiapán. Como el nopal, el mesquite parece eterno pues, aunque se tale, renace de cualquier pedazo de raíz que haya quedado enterrado.

Mi vida ha estado ligada a los árboles, a los que he mirado como iguales, y en ellos he querido ver mi destino. El libro nº 1.000, Trombiosis, marcó un momento de crisis milenarista, con un presagio de muerte. En Quintanar de la Sierra, junto a la necrópolis de Cuyacabras, encontré un nudo de un roble antiguo tallado con unas hendiduras que prefiguraban el recorrido alternativo que habría de buscar la sangre en mi brazo derecho tras sufrir una trombosis.

TESTIGOS DE LA HISTORIA

El árbol al que más libros-caja he dedicado es el Pino de las Tres Cruces, que estaba ya en el Valle de Cuelgamuros cuando Rubens y Velázquez visitaron El Escorial en 1628; aparecía en una vista de El Escorial del primero, que se quemó. Fue durante siglos hito geográfico ―pues marcaba la linde entre los territorios de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Peguerinos y Guadarrama―, árbol vigía, lugar de leyendas y referente para caminantes. Los vientos y el paso del tiempo acabaron por abatirlo en 1991, cuando tenía cerca de quinientos años. Asistí a su tala, a la plantación de tres pinos laricios en sustitución y realicé con fragmentos de su madera varios libros ―actos simbólicos en defensa del paisaje―, tres de los cuales fueron adquiridos por los ayuntamientos citados a instancias de la Agencia de Medioambiente de la Comunidad de Madrid en el primer acto de homenaje institucional a un árbol caído recogido en mi Biblioteca del Bosque, y precedente de este renacimiento del haya roja de la Fundación Lázaro Galdiano. En la exposición, el Pino de las Tres Cruces está representado por el libro nº 438, que contiene un fragmento de su corazón lígneo.

Muchos pueblos tienen su árbol emblemático. El gran ejemplar que preside la vida cívica o que se asocia al acontecimiento histórico o religioso que más ha marcado a la villa. Fueron muchas las plazas presididas por un gran olmo. La grafiosis, como veremos, acabó con casi todos, incluyendo al conocido como “olma de Rascafría”, que finalmente fue derribado en el año 2000 por el peso de la nieve. En el libro nº 776 evoco la larga lucha del árbol con la nieve. Tenía, como el Pino de las Tres Cruces, cerca de cinco siglos de vida, y se cuenta que servía de refugio al bandolero decimonónico “El Tuerto Pirón”. No sería difícil cobijarse dentro de él, pues el proceso que la misma Agencia de Medio Ambiente eligió para conservar el árbol muerto ―completando su ahuecamiento natural y liofilizándolo― permite ver su dilatado espacio interior.

Significado cívico, y político, tiene el árbol de Guernica, el roble bajo el que el Señor de Vizcaya primero y los reyes castellanos después juraban respetar los fueros vizcaínos; hoy, el Lehendakari promete allí cumplir su cargo. Una misma historia, pero cuatro ejemplares en una línea sucesoria que arranca del siglo XIV con el “árbol padre”, que vivió hasta 1742; en su lugar se plantó el “árbol viejo”, superviviente hasta 1860 y sustituido a su vez por el “árbol hijo”, que murió en 2004 y fue reemplazado por uno de sus retoños. Recogí, antes de que fuera talado, algunas ramitas tronchadas por el viento, que forman parte del libro nº 924. El roble de Guernica es testigo del drama de una población y símbolo del pueblo vasco, es también ejemplo de respeto a la vida arbórea, y de colaboración por parte del hombre en la pervivencia de determinados ejemplares.

Significado cívico, y político, tiene el árbol de Guernica, el roble bajo el que el Señor de Vizcaya primero y los reyes castellanos después juraban respetar los fueros vizcaínos; hoy, el Lehendakari promete allí cumplir su cargo. Una misma historia, pero cuatro ejemplares en una línea sucesoria que arranca del siglo XIV con el “árbol padre”, que vivió hasta 1742; en su lugar se plantó el “árbol viejo”, superviviente hasta 1860 y sustituido a su vez por el “árbol hijo”, que murió en 2004 y fue reemplazado por uno de sus retoños. Recogí, antes de que fuera talado, algunas ramitas tronchadas por el viento, que forman parte del libro nº 924. El roble de Guernica es testigo del drama de una población y símbolo del pueblo vasco, es también ejemplo de respeto a la vida arbórea, y de colaboración por parte del hombre en la pervivencia de determinados ejemplares.

Hay dinastías de árboles de la misma manera que hay dinastías de hombres. Una idea que recoge la “senda de los robles reales” de Białowieża, en la frontera entre Polonia y Bielorrusia. Son robles de cerca de 50 metros de altura apodados con los nombres de los más celebrados reyes de Polonia y Lituania, que en muy temprana fecha protegieron la zona como reserva de caza, propiciando su conservación como la única zona de bosque atlántico original que se conserva en Europa. Estos robles son contemporáneos de los monarcas que cazaron aquí en el siglo XVI, y son los verdaderos reyes del bosque. El libro nº 938 está hecho con sus cortezas.

ABATIDOS POR CAUSAS NATURALES

He citado algunos casos de árboles que han sucumbido a las fuerzas de la naturaleza en la montaña. Pero también en la ciudad ocurre. El Jardín Botánico de Madrid, refugio de muchas especies arbóreas de gran valor, ha debido lamentar la muerte por causa natural de uno de sus emblemas: el almez llamado “El abuelo”, al que he homenajeado en el libro nº 454,Almez, silencio lejano. Además, unos hongos xilográficos tomados de su corteza aparecen en otro lamento por un árbol caído, una arizónica derribada por el viento en la plaza de Linneo de Madrid: el libro nº 1024, Las raíces de Linneo. A medio camino entre la ciudad y el campo está el bellísimo parque de El Capricho, por el que paseaba Goya, en el que viven algunos de los pinos más majestuosos de Madrid. Uno de ellos cayó en 2004, y le dediqué el libro nº 909, que recuerda a las dríadas o espíritus de los árboles, cuyas voces se confunden con el murmullo de las hojas en el viento.

Son casos aislados frente a los que adquiere dimensiones catastróficas el vendaval de viento y nieve que azotó la sierra del Guadarrama en el invierno de 1996, del 20 al 22 de enero. El vendaval tronchó, derribó, arrancó de raíz cientos de miles de pinos. Estudié entonces las formas derivadas del poder del viento: auras, signos dibujados por el aire. Emanaciones volátiles o sonidos liberados de los árboles que capturé en libros como el nº 648, Ventus increbescit, que formó parte de la exposiciónEl vendaval libera las auras.

No sólo el viento o la nieve son capaces de abatir árboles. La lenta muerte por estrangulamiento es otra causa de deceso. La fuerza de las lianas puede apreciarse en el libro nº 965, Palo de tres costillas, que conseguí en el ex-convento de Tepoztlán y que, como la especie trepadora que lo protagoniza, la cual roba la vida al árbol, tiene un destino vinculado al hurto.

SUPERVIVIENTES

Pero, a veces, ni las potentes fuerzas naturales pueden con la tenacidad del árbol que se aferra a la vida, desafiando al tiempo. Varios lugares del mundo pretenden ser cuna del árbol de Matusalén. En Dalarna, al noroeste de Suecia, hay una picea o falso abeto con 9.950 años, que ha alcanzado tan fabulosa edad porque renueva continuamente su tronco, clonándose desde la raíz y adaptándose al clima de cada época. Más viejo aún podría ser el Lagarostrobos franklinii o pino de Huon que se ha encontrado en Mount Read, Tasmania, y al que se atribuyen 10.500 años. Es otro caso de inteligencia biológica: se trata de un grupo de árboles compuesto por machos genéticamente idénticos y que se ha reproducido de forma vegetativa. Ninguno de los árboles es tan viejo, pero juntos conforman un solo organismo que sí tendría esa edad.

Aunque el más sorprendente ejemplo de supervivencia sea quizás el ginkgo de Hiroshima, que se encontraba en los jardines de un templo budista a un kilómetro del lugar en el que cayó la primera bomba atómica. Fue el único árbol superviviente en la ciudad, y floreció al año siguiente sin mayores problemas. El Ginkgo biloba es una especie única, antiquísima, que puede llegar a vivir mil años. Se considera como un fósil viviente, y si pudo sobrevivir a la radiación es porque posee una resistencia a la oxidación adquirida hace muchos millones de años, cuando la atmósfera era más rica en oxígeno que en la actualidad.

La supervivencia más allá de lo esperable no es exclusiva de las especies paleontológicas. En cada bosque antiguo no es raro encontrar a algún anciano que suma siglos. Casi huecos, aparentemente frágiles, siguen dando hojas. Entre los que he conocido figuran el roblón de Estalaya, en Palencia, erguido a pesar de las heridas de los rayos (libro nº 968) o multitud de castaños asturianos, cuyos huecos son tratados con fuego para evitar la descomposición (libro nº 1006). Los castaños figuran, de otro lado, entre los árboles nutrientes, que durante siglos alimentaron a los habitantes del norte de España, y seguramente por eso han sido especialmente cuidados y han llegado a ser tan viejos.

TUMBADAS

Los árboles nos dan de comer y nos surten de madera. Entre las muchas cortas que se realizan con el fin de explotar su madera hay grandes tumbadas de miles de árboles. Casi nunca somos conscientes de que estamos rodeados de árboles muertos en forma de muebles, objetos que incluyen aglomerado, o papeles. En el libro nº 630, Cortezas incensadas, hice una ofrenda por todos esos pinos anónimos, sacrificados como en una gran hecatombe para nuestro aprovechamiento.

En muchos lugares, y en diversos momentos de la historia, ese aprovechamiento adquiere carácter depredatorio. Es notable el caso del palo de Campeche (Haematoxylon campechianum) en la península

del Yucatán, que fue motivo de un largo enfrentamiento entre españoles y británicos. Árbol tintóreo (produce un atractivo negro azulado), era muy demandado por la industria textil europea, y España quiso monopolizar su comercio. Pero los piratas que quedaron sin oficio ni beneficio tras el Tratado de Madrid, en 1667, y se instalaron en la zona del Caribe descubrieron la rentabilidad de la corta en las zonas menos vigiladas y se reconvirtieron en piratas taladores, con sede principal en Belice y con el beneplácito de la corona inglesa. No hace falta decir que la actividad forestal de los españoles en América no fue menos dañina que la de los contrabandistas.

Se cortan los bosques también para abrir espacio a diversos cultivos, o a plantaciones de árboles de rápido crecimiento como el eucalipto. El mundo se preocupa por la tala de los bosques amazónicos, pero también recientemente se ha llamado la atención sobre la acelerada desaparición de los bosques del valle de Florentine, en Tasmania, donde los Eucaliptus regnans, que alcanzan los 90 metros de altura, y los prehistóricos helechos arborescentes, ambos integrantes del antiguo bosque austral ya muy diezmado, están siendo arrasados para plantar eucaliptos genéticamente modificados para la explotación de la pulpa de madera. Más cerca de nosotros, en Galicia, los bosques autóctonos hace tiempo que han sido arrinconados por las plantaciones de eucaliptos nacidos para morir pronto, y dañinos para los territorios ajenos al suyo original. A uno de ellos, el Eucalipto marcado en Boaventura (libro nº 758), que con seguridad ya no estará vivo, le contaba mis sueños más vívidos, y dibujé sobre él un signo protector.

LA AMENAZA

Las culturas más avanzadas cuidan los árboles porque aprecian su belleza y valoran su utilidad. Un respeto que se impone desde antiguo. Tenemos un ejemplo en las penas descritas en la literatura canónica india a los que atentaban contra ellos. Se habían de pagar multas elevadas por cortar árboles junto a los caminos y las fuentes, o por arrancar hierbas sin motivo. El Kurma Purana señala las penitencias para purgar la culpa de quienes corten un árbol, enredadera, matorral o cualquier tipo de planta. En el Agni Purana se decreta castigo corporal por cortar árboles umbríos como el baniano o el mango. El Vayu Purana afirma que la tala masiva de bosques provoca catástrofes naturales.

Nos escandalizan las talas en los bosques, pero deberían dolernos lo mismo los crímenes contra los árboles que se cometen en el entono urbano. Frente al Museo de Historia Natural de Berlín hay un grupo de enormes hayas rojas que conservan toda su copa. Son paradigma de la actitud de respeto y admiración hacia los árboles por parte de una ciudad. Madrid desprecia y mutila todos los árboles con cortas a traición y podas asesinas. Con ese espíritu arboricida tan español.

Uno de los mayores enemigos de los árboles es la construcción. Todos conocemos la amenaza que pesa sobre los plátanos del Paseo del Prado, debido a que el proyecto urbanístico no había tenido en cuenta que esa masa vegetal debe ser intocable. Incluí sus cortezas, castigadas por la contaminación, en el libro nº 998, Lo que sienten los plátanos del Paseo del Prado. También en las construcciones a menor escala los primeros en caer son los árboles, en ocasiones de gran porte. En muchas casas pequeñas y medianas había, en los patios interiores, higueras. Una de ellas estaba en la calle Málaga y, antes de que fuera levantada por las excavadoras, de ella recogí materiales para hacer unos dibujos y el libro nº 673. En la zona de Pinar del Rey los jardines son sacrificados para ganar superficie construida y, a unos metros de mi estudio, el que fue hermoso vivero de Bourguignon, un remanso de frondosa humedad, se ha vendido a la presión del ladrillo y ha perdido ―o perderá debido al daño ocasionado en las raíces― grandes ejemplares. Es sólo uno de los miles de ejemplos de árboles caídos en jardines privados con consentimiento de las autoridades.

RITUALES DE CRECIMIENTO, CONSERVACIÓN Y PROTECCIÓN

Cuando un árbol o un bosque de mi entorno, con los que tengo una relación habitual, está en peligro o ha sufrido algún percance, actúo mediante sortilegios plásticos para propiciar su renovación. No son ritos que tengan lugar en el territorio sino en mis cajas. El primer ejemplo de esta práctica en mi Biblioteca del Bosque es el libro nº 228, Cómo provocar el crecimiento del cedro cortado en Villa Ródenas, en un jardín de Cercedilla. Transitar por los árboles a diario crea un vínculo con ellos cuya ruptura produce sufrimiento. Algún tiempo después, en la misma puerta de mi estudio serrano cayó un pequeño nogal para el que oficié un enterramiento en el libro nº 368.

En ocasiones, las especies luchan infructuosamente contra enfermedades y plagas que no son combatidas con la suficiente energía por las autoridades medioambientales. La grafiosis, ya mencionada, hizo descender entre un 80 y un 90 % la población de olmos ibéricos a partir de los años 80, y los pocos supervivientes son mimados para retrasar su fin y poder tener un banco genético para su recuperación. La enfermedad es producida por el hongo Ceratocystis ulmi, de carácter semiparasitario, transmitido por un escarabajo conocido como barrenillo del olmo. El libro nº 251, La leyenda del olmo pez,contiene un trozo de madera de un gran olmo, atacado por la grafiosis, desaparecido junto a la estación de trenes de Cercedilla.

Otro escarabajo, el Cerambyx cerdo o capricornio de las encinas, está produciendo daños devastadores en los encinares del sur y del oeste de la Península, muy debilitados por la seca y las malas podas realizadas tiempo atrás. Es muy difícil de tratar, pues la larva de gran tamaño vive durante dos años en el interior de la encina, taladrando y pulverizando su madera, y haciéndola muy vulnerable a la sequía creciente y a los vendavales que las tronchan con enorme facilidad. He conocido de cerca el problema en el Valle de Alcudia, Ciudad Real, y he hecho varios libros en los que protejo simbólicamente a las encinas incrustando fragmentos de cuarzo blanco de Monterrubio de la Serena, Badajoz, en las galerías devoradas por las larvas (libro nº 830) o intercalando trozos de selenita transatlántica entre trozos de corteza (libro nº 995). En el libro nº 954 hay Cúpulas sinfónicas de encinas, recolectoras de sonidos amenazantes, que navegaron a orillas del Ganges y se depositaron sobre la arena del crematorio de Marikarnika, en Veranesi. Este sortilegio musical se relaciona también con el lenguaje cifrado, secreto, que contiene el picón de encinas del libro nº 916.

Hay otras especies amenazadas. El pino insignis sufre en la cornisa cantábrica el llamado “cáncer del pino”, causado por otro hongo, el Fusarium circinatum, procedente de Estados Unidos. Pero finalmente, el mayor enemigo de los pinos es el ser humano, y para defenderlos de él trazé líneas de defensa con azufre en el libro nº 412. De la misma manera, esparcí esperma de ballena entre las hayas de Alkiza, Guipúzcoa, para contribuir a su fertilidad y preservación, en el libro nº 923.

SALVACIONES

Hace tres siglos, en Rajastán, India, Amrita Diva lideró a más de trescientas mujeres que sacrificaron sus vidas abrazándose a los árboles para salvarlos de la corta. Su espíritu vive en los integrantes del movimiento Chipko (la palabra significa “abrazar”), iniciado en 1972 por dos seguidoras de Gandhi y las mujeres de Gashwal (Uttar Pradesh) con los mismos fines. También ellas se abrazan a los árboles para conservarlos.

El afán de conservación de la naturaleza se fundamenta en el amor a los árboles, y ha tenido a lo largo de la historia grandes campeones. Admiro particularmente a John Muir, que promovió la protección de Yosemite Valley y otras áreas, y es uno de los padres del ecologismo. Le recuerdo en el libro nº 387, Claustro para un nudo de pino rojo, que contiene un pedazo de Sequoya sempervirens del bosque de Muir en Mill Valley.

Es menos conocido el caso de la protección del bosque de Fontainebleau por parte de los artistas. La primera causa de su conservación fue la de su condición de reserva de caza de propiedad real, inalienable desde el siglo XVI. En 1682, 1720 y 1802 se realizaron plantaciones para hacerlo más frondoso. Entre 1831 y 1848 se reforestó intensivamente con pino silvestre, a lo que se oponían los pintores de la escuela de Barbizon que hicieron del lugar su arcadia. En 1837 consiguieron revocar la corta de los árboles más antiguos y evitaron los pinos en sus rincones preferidos. Esa sensibilidad hizo que, ya en 1853, 624 hectáreas de bosque antiguo fueran protegidas y en 1861 se creó una Serie Artística de más de mil hectáreas a través del primer estatuto de protección de la naturaleza del mundo. El del parque Yellowstone es de 1872.

También he de homenajear a Aldo Leopold, ingeniero forestal y precursor del ecologismo en Estados Unidos, que se dedicó a la repoblación de pinos en la granja familiar de Shacq. Murió de un ataque al corazón el 11 de abril de 1948, mientras intentaba apagar un incendio en la granja de un vecino, que amenazaba sus plantaciones. Su obra cimera es el Almanaque del Condado Arenoso, publicado en 1949 poco después de su muerte, con el que se funda la ética ecológica como disciplina filosófica.

Mis actuaciones en el campo del conservacionismo han sido misiones salvíficas más sigilosas. El libro nº 523, Sacrificio, forma parte de una serie sobre la salvación de la corta de un importante conjunto de pinos en mis bosques del Valle de la Fuenfría. En el invierno de 1992 se marcó allí una numeración de corta según el método tradicional de sacar un trozo de la corteza y escribir un número en los árboles que serán talados. Eran 991 pinos en Los Helechos, una zona de bosque profunda y sombría, casi inalterada. Me propuse salvar los pinos que por su antigüedad, majestuosidad, formas y rareza consideré que debían seguir existiendo. Para ello camuflé el tajo que se da al tronco para estampar la numeración. Quitaba el número de un pino de gran fuste o belleza y lo pasaba a otro más pequeño. Esto descolocaba a los forestales, que no se decidían a iniciar el trabajo. No estando seguro de la eficacia de este método, me dirigí al responsable de la Agencia de Medio Ambiente, Juan Vielva, solicitando la salvación de doce pinos, que fueron borrados de la lista. Finalmente, conseguí evitar la totalidad de la corta.

Mis actuaciones en el campo del conservacionismo han sido misiones salvíficas más sigilosas. El libro nº 523, Sacrificio, forma parte de una serie sobre la salvación de la corta de un importante conjunto de pinos en mis bosques del Valle de la Fuenfría. En el invierno de 1992 se marcó allí una numeración de corta según el método tradicional de sacar un trozo de la corteza y escribir un número en los árboles que serán talados. Eran 991 pinos en Los Helechos, una zona de bosque profunda y sombría, casi inalterada. Me propuse salvar los pinos que por su antigüedad, majestuosidad, formas y rareza consideré que debían seguir existiendo. Para ello camuflé el tajo que se da al tronco para estampar la numeración. Quitaba el número de un pino de gran fuste o belleza y lo pasaba a otro más pequeño. Esto descolocaba a los forestales, que no se decidían a iniciar el trabajo. No estando seguro de la eficacia de este método, me dirigí al responsable de la Agencia de Medio Ambiente, Juan Vielva, solicitando la salvación de doce pinos, que fueron borrados de la lista. Finalmente, conseguí evitar la totalidad de la corta.

En Madrid, algunos de los que vivimos en el entorno del Pinar del Rey, uno de los pocos reductos de pinar salvaje en la ciudad, con más de doscientos años de antigüedad, tuvimos que manifestar nuestra oposición a su tala parcial para abrir un apeadero del metro, consiguiendo la paralización del proyecto. El pinar está situado en el punto más alto de la ciudad, y se llama así porque por allí paseaba Alfonso XII (y hasta cazaba Franco). Borré las marcas rojas que señalaban los pinos a cortar y realicé diagramas protectores con sus piñones en dos libros; uno de ellos es el nº 790. Ambos formaron parteposteriormente de una exposición de arte español de los noventa en el palacio del Senado. Hablaron allí. De ese mismo pinar recogí un brinzal que brotaba de un piñón que se había desprendido de un árbol cortado y que incluí en la caja del libro nº 1014, Pinos y susurros, como testimonio de esperanza en la conservación de este espacio natural.

***********

Los árboles tienen siempre las de perder ante el hombre. Ya dijo Victor Hugo que produce una enorme tristeza pensar que la naturaleza habla mientras el género humano no escucha. Pero hay que confiar en que el cambio de las mentalidades y los avances científicos nos ayuden a cuidarla cada vez mejor. En un futuro quizá sea habitual la clonación de grandes ejemplares o de árboles históricos; ya se está haciendo en Nueva York con un haya europea de cien años que crece en Cherry Hill, dentro de Central Park. Quién sabe lo que depara la investigación espacial en materia botánica, pero ya tenemos “árboles lunares”, crecidos a partir de semillas que viajaron a la Luna en el Apolo XIV. Tal vez llevemos semillas de la Tierra a la Luna. En Noruega se ha creado una cámara global de semillas, cerca de Longyearby, excavada en el corazón de una montaña congelada en el Ártico para preservar todos los tipos de semillas del mundo.

Miguel de Unamuno escribió: “Hubo árboles antes de que hubiera libros, y acaso cuando acaben los libros continúen los árboles. Y tal vez llegue la humanidad a un grado de cultura tal que no necesite ya de libros, pero siempre necesitará de árboles, y entonces abonará los árboles con libros”.

Sea cual sea el futuro, la única conclusión a la que he llegado es ésta: siento devoción por todos los árboles pero estoy enamorado de los pinos. Y, además, siento una especial fascinación por el haya roja.

Árboles caídos, árboles siempre vivos.

MIGUEL ÁNGEL BLANCO

With an ancient history, trees are one of the firm hubs of material and spiritual life for many cultures. Nowadays they still constitute a great source of knowledge for those who understand their value and feel their energy. My Forest’s Library, which was begun in 1985 and is made up today of 1055 box-books, has been constructed around this hub, always from the starting point of personal experiences, although it includes many other organic and inorganic forms. The death of the copper beech (Fagus sylvatica var. Purpurea) in the Flower Garden of the Fundación Lázaro Galdiano is the reason for this exhibition, which contemplates my relation with arboreal individuals of particular relevance due to their antiquity, their legendary character, their role in my vital and artistic environment. My devotion towards them. They are trees that have been lived and dreamed and whose existence is immortalized in my Library. Together they constitute a forest of impressive presences. Homage, protection and renewal have been the more frequent dialogue forms with them.

The archaeological findings, the Natural History museums and the prehistoric species still alive today reveal the wisdom with which trees have confronted geological and climatic adversities. Some species last longer than others, but there have always existed individuals with a special endurance to time, venerated because of their antiquity. When their life ends due to natural causes, we have to admit the justice of vital cycles and admire the power still held by the fallen tree. But trees, beyond their sustainable exploitation for the obtainment of wood, suffer man´s threat. Nature’s excellence has given us trees and our duty is to preserve them. Instead, we witness how great forest areas are depleted and, at a more local level, how trees in streets and parks are treated with contempt. The copper beech of the Flower Garden, more than a hundred years old, dried up for several reasons, among them the building repairs of the palace and a dire “landscape” work, which cut off part of the secondary roots. The dismay of the employees of the Fundación Lázaro Galdiano and of all those who knew and loved this magnificent specimen was great. The possibilities of saving the tree were studied, but found unfeasible. The Dirección General de Bellas Artes of the Ministerio de Cultura, together with the Fundación, then resolved to put me in charge of an artistic project for somehow keeping the presence of the tree alive. The first thing I did was to have an audience with the beech, which took place on December, the 7th, 2007, so as to communicate with its power, to feel it and interpret it. I also visited the other specimen of centenarian beech in Madrid, which lives magnificently in the Royal Botanical Gardens. And I undertook an expedition to the Beech wood of Montejo, frozen. After this conclave of beeches, the communication code we chose was moist silence, lightness and transparency. The project, the rebirth of the beech, will be luminous shadow and ice, light and frosted glass.

Just like a tree can never be observed from a sole point of view, the memorial of the beech was to have various perspectives, expressed by different means, visible from different places and with diverse day and night light conditions. Therefore, three interventions in the garden subtly evoke the now ghostly presence of the tree. The first one is the projection of the silhouette of the dry beech on the museum’s turret. At dawn, the luminous shadow of the absent tree begins to emerge on the building’s façade that faces the garden, centred on the turret. A potent floodlight has been installed, which shows not the shadow, but the negative of the shadow, that is, a figure of light. The second intervention has fixed by acid etching on the great window of the shop the part of the tree’s image one could see from the inside through this window – approximately from the centre of the room. This type of work is linked to the important collection of glass and crystal objects in the museum. The third one, of which I am only promoter and witness, closes the vital cycle with the planting of a new copper beech brought, like the dead one, from Navarra, the birthplace of Lázaro Galdiano.

The project is completed by the realization of two box-books of the Forest’s Library with material from the beech: One with the last leaves and one with its inner wood. And with the exhibition Árbol caído (‘Fallen Tree’) in the exhibition room of the Fundación Lázaro Galdiano, a nocturnal path by the ancient or fallen trees I have known and lived. Box-books which contain fragments of these trees and their experiences. Their journey to the Beyond.

I have divided the exhibition in different sections, reuniting trees classified in diverse categories.

Stone Trees

They are the fascinating fossil trees, fallen and eternized by petrifaction. In April, 2007, the oldest tree known today, 385 million years old, was discovered. It lived at a time when not even dinosaurs had appeared on earth, much less man. Its only companions were arthropods. It is a specimen of Wattieza cladoxylopsid from the Devonian, a type of arborescent fern found in the county of Schoharie, New York State. It is almost nine meters high and, exceptionally, it still has branches and roots; it was still standing when it was covered by sediments and afterwards fossilized. Equally impressive are the petrified forests in the northeast of the province of Santa Cruz, in the Argentinean Patagonia, which are younger – approximately 130 million years old – and therefore more evolved trees, similar to araucarias. At the beginning of the Cretaceous, volcanic eruptions buried these trees with ashes, and some trunks remained standing, nowadays forming great fossil groups.

In Spain we have a fossil tree site near the village of Hacinas, in the Sierra de la Demanda, of the same antiquity as the Patagonian one. In those times, Burgos enjoyed a hot and humid tropical climate that allowed the development of a dense jungle with a variety of conifers of the family of the Podocarpaceous, which could reach a height of up to 80 meters.

For many years I have been interested in the fragments of fossil trunks and branches that trap the infinite age of trees, and I have reunited a small collection of them. I have used them in some books, like Nr. 312, Astillas de un bosque petrificado en Albacete (‘Splinters of a Petrified Forest in Albacete’), or Nr. 779, Tremor en el castaño de El Tiemblo (‘Quaver in the Chestnut Tree of El Tiemblo’), where I included two slices of petrified wood from Madagascar, 80 million years old, with some chestnuts of the centenarian “El Abuelo”.

Mystical, Legendary and Prophetic Trees

The tree is a universal symbol. A fountain of wisdom, it has a prominent role in the ceremonies of many cultures and religions and plays a part in numerous mythical narratives. It participates in different cosmogonies, in the founding history of cities, in revelations, in historic or imaginary epic poems. Trees that existed or not, but that are alive in memory; examples of surprising perpetuity, because of their association with archaeological remains or because of the care with which many generations kept the sprouts of these venerable specimens alive.

One of the most famous trees is the Pipal, or Boddhi tree, under which Siddhartha Gautama was transformed into a Buddha when reaching enlightenment, in Boddhgaya, Bihar State, India. In the place it grew now lives a descendant of it, with six of whose leaves I created Book Nr. 740, Ficus religiosa, the scientific name of this type of fig tree. Tradition reports that after enlightenment Buddha remained one whole week sitting in meditation in the same place; the second week he meditated walking and the third one he spent contemplating the Pipal. The tree survived for centuries and has many descendants in India and other Buddhist countries: The one that flourishes in the Mahavira Monastery of Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka, is especially revered.

Trees have also played a capital role in desert countries, like Egypt. Hatshepsut tried to justify the usurpation that raised her to power and to win the favour of Ammon’s priests by offering them frankincense, a resin, which constituted an indispensable ritual substance. She organized a great sea expedition to Punt to take the incense tree (Boswellia sacra) to Egypt, sending five great ships of splendid Lebanon cedars, with 9 meter high masts. She considered this journey the culmination of her reign, and so it was reflected in the exquisite reliefs of her funerary temple in Deir el-Bahari, of great ethnographic and botanical interest. The temple was surrounded by ponds and gardens and there still remain the stumps of the old trees planted by the queen. From them I removed some splinters, preserved in Book Nr. 1028, El árbol del incienso de Hatsheput (‘The Incense Tree of Hatshepsut’).

Religious sites not only included trees in their gardens, but reached their traditional architectonical forms by development of the vegetal constructions where ancestral ceremonies were performed. Thus, for instance, in the funerary complex of Zoser, in Saqqara, the architect Imhotep imitated the trunks of palm trees or papyrus in the ribbed columns. Two old wood trunks protrude from the Eastern façade of the step pyramid, whose hot stones I climbed to obtain three splinters, kept in Book Nr. 1027, Árbol interior Saqqara (‘Inner Tree Saqqara’).

The incense trees of Hatshepsut were taken to Karnak, but they are not the only ones that grew and grow in the most sacred site of Egypt. In the northern section, far from the turmoil of the visitors, one of the three chapels of the Ptah temple is dedicated to the goddess Hathor, who lives there as one of her manifestations, the solar lioness Sekhemet; it is an imposing black granite statue immersed in darkness, illuminated from above by the sunset light of Thebes. At the door of this temple grows a sycamore, which was the tree associated with Hathor: One of her titles was “Lady of the Sycamore”. It is very possible that this tree, from which I took the dripping figs and small branches that can be seen in Book Nr. 1035, Sicomoro Sejemet (‘Sejemet Sycamore’), could be a descendant of the ones that probably surrounded the construction in times of the pharaohs. The sycamore, on the other hand, was a much appreciated species by the Egyptians because its wood was the best for sarcophagi, conferring the death eternal life. The Book of the Death expresses it as follows: “I have embraced the sycamore and the sycamore has protected me; the doors of Duat have been opened for me.” On top of that, the fibres were used to weave amulet cords for the living and the death.

Mysticism and trees often go together. At the highest point of Segovia’s monastery of Discalced Carmelites stands the skeleton of a cypress – another funerary tree – planted there by Saint John of the Cross in the XVI century. Splinters of its dry wood, taken at the light of dawn reflected by the river Eresma, inflamed water and splinters from the shoots of its roots are collected in Book Nr. 1047, Ciprés de San Juan de la Cruz (‘Cypress of Saint John of the Cross’). Saint John planted another cypress, still alive, in the Carmen de los Mártires, Granada, under whose shadow he wrote Dark Night of the Soul. The botanical lack of definition of the trees planted by the saint is curious. The one in Granada is traditionally known as “the Cedar of Saint John of the Cross”, and the one in Segovia would be, in words of the guardian of the high chapel, a juniper-cypress (?) of incorruptible wood.

The cypress is a symbol of longevity, and in ancient China its seeds were consumed to attain it; it was also affirmed that if one rubbed one’s heels with its resin, one could walk on the sea. The oldest cypress of the city of Granada, 600 years of age and dried up by now, is in a courtyard of Generalife, to which it gives name: It is the “Cypress of the Sultana”, paradigm of a tree category that propitiates secret meetings. Under this cypress, so the legend goes, Boabdil’s wife met her lover; the vengeance the king took on all the members of the traitor’s family is one of the most beautiful legends of the Alhambra. The legend says that the cypress was killed by lightning, and it is remembered in Book Nr. 1052.

Trees and shamanism also go hand in hand. In Book Nr. 392, Raíz del Nagual (‘The Nagual’s Root), whose box contains fragments of an ancient walnut tree knocked down by the wind, I remember the animal spirit, vehicle of the gods, which gives power to the shamans and which, in the Toltec tradition, is the projection each being possesses since birth, that protects and guides him. Nagualism affirms that trees are nearer to man than ants. Trees and human beings share emanations. The old seers developed witchcraft techniques to trap the conscience of trees, using them as guides to enter the deepest levels. The walnut tree is my nagual. In the branch contained in the book I pierced a trapezoidal form similar to the ones I have seen in ancient representations of Mexican shamans.

At the principal entrance of Sonora’s market, specialized in healing plants and sorcery, I obtained some strange fragments of dark striped wood they sold to me as “viper tree”, a remedy for infections and fungus. I have classified the book I created with them, Nr. 794, in the group of mythical trees, because I haven’t been able to identify this healing or magic species. I only found a study about healers of Veracruz, where a “viper tree” is described as Erythrina Americana. As far as I know, it doesn’t correspond with the splinters I have. Involuntarily, I have shared the mystery with people who have seen a reproduction of my book in some catalogue and I have been questioned about it, but wasn’t able to answer.

In Mexico, trees are in the origin of the founding of cities. Tenochtitlan (nowadays Mexico City) was constructed in the site indicated by the legendary eagle, which, after hundreds of years of pilgrimage, alighted on a nopal to devour a serpent in the year 1325. I dedicated Book Nr. 799, La gran Tenochtitlán (‘Great Tenochtitlan’), with fragments of nopal root from Zacatecas, to this episode (not included in the exhibition). The nopal is not really a tree, but belongs to the cactus family – although the old specimens lose their lower leaves and grow from a ligneous stem – and its capacity for renovation turns it into a symbol of immortality. A tree is the great mesquite (from the Nahuatl mizquitl) that grows near the Templo de Santa María Magdalena in Tequisquiapan. History tells that the founding mass of the city was celebrated under it in 1551; but the community existed before and there is a legend, probably inspired in the old one of Mexico City, that another founding eagle alighted on the mesquite in Pre-Hispanic times; the husks of its seeds are in Book Nr. 921, Mesquite, árbol fundador de Tequisquiapán (‘Mesquite, Founding Tree of Tequisquiapan’). As the nopal, the mesquite seems eternal because, even if it is cut down, it sprouts again from any root fragments that remain buried.

My life has been united to trees, which I have considered as my equals, and in them I have seen my destiny. Book Nr. 1000, Trombiosis, marked a millennium crisis, with a presage of death. In Quintanar de la Sierra, near the necropolis of Cuyacabras, I found a knot of ancient oak, engraved with some slits that prefigured the alternative path blood had to create in my right arm after suffering a thrombosis.

Witnesses of History

The tree to which I have dedicated more box-books is the Pino de las Tres Cruces (‘Pine of the Three Crosses’) that already existed in the Valle de Cuelgamuros when Rubens and Velázquez visited El Escorial in 1628; it appeared in a painting of the Monastery that burned down. For centuries it constituted a geographic landmark – it determined the border of the territories of San Lorenzo del Escorial, Peguerinos and Guadarrama. It was a lookout tree, a legendary site and a reference for travellers. The winds and the passage of time finally knocked it down in 1991, when it was almost 500 years of age. I witnessed its felling, the planting of three Pinus nigra in substitution and I created several books with pieces of its wood – symbolic acts in defence of the landscape -, three of which were purchased by the cited town halls in the first institutional act of homage to a fallen tree collected in my Forest’s Library, and a precedent of this rebirth of the copper beech in the Fundación Lázaro Galdiano. In the exhibition, the Pino de las Tres Cruces appears in Book Nr. 438, that contains a piece of its ligneous heart.

Many villages have their emblematic tree, the great specimen that presides over civic life or that is associated to the historic or religious event that most marked the place. Many town squares were presided by a great elm tree. Graphiosis, as we will see, killed almost all of them, including the famous «Olma de Rascafría», which was finally knocked down by the weight of the snow in the year 2000. In Book Nr. 776, I remember the long fight of the tree against the snow. It had, as the Pino de las Tres Cruces, almost five centuries of age and it is said that it was the refuge of the bandit «El Tuerto Pirón» in the XIX century. It wouldn’t have been difficult to take refuge under it, as the process that the selfsame Agencia del Medio Ambiente chose to preserve the dead tree – completing its natural cavity and lyophilizing it – allows to see its ample inner space.

The tree of Guernica has civic and political significance. Under it, the Lord of Biscay first and the Castilian Kings afterwards swore to respect the Biscayan codes of laws. Nowadays, the Lehendakari swears there to fulfil his post. The same history, but four specimens in a lineage that begins in the XIV century with the «father tree», that lived until 1742; in its place they planted the «old tree», which survived until 1860 and was substituted by the «son tree», that died in 2004 and was replaced by one of its sprouts. Before it was felled down, I collected some twigs broken by the wind, which form part of Book Nr. 924. The Oak of Guernica, witness of a city’s drama and symbol of the Basque people, also constitutes an example of respect for arboreal life and of the human assistance in the survival of some specimens.

There are tree lineages in the same way that there are human lineages, an idea developed in the «path of the royal oaks» of Bialowieza, the frontier between Poland and Byelorussia. They are oaks of approximately 50 metres of height, which bear the names of the most famous kings of Poland and Lithuania, who at an early time protected the site as a hunting reserve, propitiating so its conservation as the only area of original Atlantic forest still existing in Europe. These oaks are contemporary of the monarchs that hunted there in the XVI century and are the true kings of the wood. Book Nr. 938 is made with their barks.

Death by Natural Causes

I have mentioned the cases of some trees that succumbed to the forces of nature in the mountains. But it also happens in the city. Madrid’s Botanical Gardens, a refuge for many tree species of great value, lamented the death by natural causes of one of its symbols: The hackberry named «El abuelo» (‘The Grandfather’), to which I paid homage in Book Nr. 454, Almez, silencio lejano (‘Hackberry, Distant Silence’). Some xylographic fungi taken from its bark appear in another lament for a fallen tree, an Arizona cypress knocked down by the wind in Madrid’s Plaza de Linneo: Book Nr. 1024, Las raíces de Linneo (‘Linneo’s Roots’). Halfway between the city and the fields is the beautiful park of El Capricho, where Goya walked, inhabited by some of Madrid’s most majestic pines. One of them fell in 2004, and I dedicated Book Nr. 909 to him. In this book I remember the dryads, or spirits of the trees, whose voices merge with the murmur of the leaves.

They are isolated cases, in comparison with the catastrophic snowstorm that pounded upon the Sierra de Guadarrama in January 1996, from the 20th to the 22nd. The gale broke, knocked down and uprooted pines by the thousands. On this occasion I studied the forms derived from the power of the wind: Auras, signs drawn on the air. Volatile emanations or sounds liberated by the trees, which I captured in books like Nr. 648, Ventus increbescit, that was part of the exhibition El vendaval libera las auras (‘The Gale Liberates The Auras’).

Not only wind and snow are capable of knocking down trees. The slow death by strangulation is another death-cause. The force of vines can be appreciated in Book Nr. 965, Palo de tres costillas (‘Stick of Three Ribs’), which I got at the ex-convent of Tepoztlán, and which, like the protagonist species, that steals life from the tree, has a destiny united to theft.

Survivors

But sometimes not even natural forces are able to prevail over the firmness of the tree that clings to life, defying time. Several places on Earth claim to be the birthplace of Metusalem. In Dalarna, to the northwest of Sweden, lives a Picea abies, or Norway spruce, of 9 950 years, that has reached such a fabulous age because it constantly renovates its trunk, cloning from the root and adapting to the climate of each era. The Lagarostrobos franklinii, or Huon Pine fount at Mount Read, Tasmania, could be older still, with a probable age of 10 500 years. It is another case of biological intelligence: It is a group of trees made up of genetically identical males that reproduce vegetatively. None of the trees by itself is so old, but together they form a single organism that would be this age.

Although the most surprising example of survival is probably the gingko of Hiroshima, which grew in the gardens of a Buddhist temple one kilometre from the place where the first atomic bomb fell. It was the only surviving tree of the city, and blossomed the year afterwards without any problem. Gingko biloba is a unique species, very ancient, that can reach 1000 years of age. It is considered a living fossil and it could survive the radiation because it acquired great resistance to oxidation many millions of years ago, when the atmosphere had a greater content in oxygen than today.

Survival beyond what is to be expected not only happens to paleontological species. In every ancient forest it is not rare to find some ancient exemplars. Almost hollow, apparently fragile, they still grow leaves. Among the ones I have known is the oak of Estalaya, in Palencia, standing up in spite of the wounds left by thunderbolts (Book Nr. 968) or many Asturian chestnuts, whose hollows are treated with fire to prevent decomposition (Book Nr. 1006). Chestnuts, on the other hand, belong to the group of nutrient trees, which have always fed the inhabitants of the north of Spain. Maybe this is the reason they were especially cared for and could reach such an advanced age.

Fellings

Trees give us food and provide wood. In the many fellings carried out to obtain it, sometimes thousand of trees are cut down. We are almost never conscious that we are surrounded by dead trees in the form of furniture, objects made of plywood or paper. In Book Nr. 630, Cortezas incensadas (‘Incensed Barks’) I made an offering to all those anonymous pines, sacrificed as in a great hecatomb for our own profit.

In many places and at different points in history, this exploitation reaches a predatory character. One outstanding case is that of the logwood (Haematoxylon campechianum) of the Yucatan peninsula that constituted the reason for a long conflict between Spaniards and British. A dyeing tree (it gives an attractive bluish black), it was needed by the European textile industry, and Spain tried to corner the market. But the pirates that got out of work after the Treaty of Madrid in 1667 and went to live to the Caribbean discovered the income-yield capacity of felling these trees in less controlled areas and transformed themselves into felling pirates, with headquarters in Belice and with the approval of the English Crown. Needless to say, the activity of the Spaniards was as harmful as that of the contrabandists.

Trees are also cut down to make space for other crops or for plantations of fast growing trees, like eucalyptus. The world worries because of the deforestation of the Amazonian rainforest, but recently attention has turned to the accelerated disappearance of the forests in the Tasmanian Florentine Valley, where the 90 meters high Eucalyptus regnans and the prehistoric tree ferns, both part of the decimated ancient austral forest, are being destroyed to plant genetically engineered eucalyptus trees, to exploit the wood pulp. Nearer to us, in Galicia, the native forests have long since been cornered by plantations of eucalyptus trees, born to die fast and harmful for territories other than their original one. To one of them, the Eucalipto marcado en Boaventura (‘Eucalyptus marked in Boaventura’, Book Nr. 758), already dead for sure, I related my most vivid dreams and I drew on him a protective sign.

The Menace

Advanced cultures care for trees, because they value their beauty and utility. A respect that is instilled since ancient times. We find an example in the punishments described in Indian literature for those that attempted against them. People had to pay high fines if they cut down trees by roadways and fountains or if they uprooted herbs without good reason. Karma Purana indicates the penance for expiating the guilt of those that cut a tree, vine, bush or any type of plant. In the Agni Purana bodily punishment is decreed for felling shady trees like the Banyan or the Mango tree. The Vayu Purana affirms that the massive felling of trees causes natural disasters.

We are upset by deforestation, but we should grieve as much for the crimes committed against trees in urban environments. In front of Berlin’s Museum of Natural History there is an enormous group of copper beeches that still have their whole crown. They are a paradigm of an attitude of respect and admiration towards trees from the part of a city. Madrid despises and mutilates trees with treacherous fellings and murderous pruning. With this tree-killing spirit that is so Spanish.

One of the tree’s greatest enemies is construction. We all know the menace that threatens the plantains of the Paseo del Prado, because in the city-planning project it had not been considered that these trees should be untouchable. I included their barks, affected by pollution, in Book Nr. 998, Lo que sienten los plátanos del Paseo del Prado (‘What Paseo del Prado’s Plantains Feel’). Also in smaller constructions the first to die are the trees, sometimes of great size. In many small and middle sized houses there were fig-trees in the inner courtyard. One of them lived in Calle Málaga, and before it was uprooted by the excavator, I took materials for some drawings and Book Nr. 673. In the neighbourhood of Pinar del Rey, gardens are sacrificed to gain constructed area and, just a few meters from my study, the former beautiful tree nursery of Bourgignon, a meadow of leafy moisture, has sold itself to the pressure of bricks and has lost – or will lose, because of damage to the roots – great specimens. It is just one of the thousands of examples of trees that died in private gardens with the compliance of the higher instances.

Rituals of Growth, Conservation and Protection

When a tree or a forest in my environment, with which I have a habitual relationship, is endangered or has suffered some misfortune, I take action by means of plastic spells to propitiate its recovery. Normally they are not rites realized in the territory, but in my boxes. The first example of this practice in my Forest’s Library is Book Nr. 228, Cómo provocar el crecimiento del cedro cortado en Villa Ródenas (‘How to Provoke the Growth of the Cedar Tree Cut Down in Villa Rodenas’), a garden in Cercedilla. To daily pass the trees establishes a bond, whose rupture creates suffering. Sometime later a small nut tree fell at the door of my mountain study, for which I officiated an interment in Book Nr. 368.

Sometimes the species battle vainly against illnesses and plagues that are not tackled with sufficient energy by the environmental authorities. The already mentioned graphiosis lowered the population of Iberian elms between 80 and 90% in the 80ties, and the few survivors are pampered to delay their death and obtain a genetic bank for their recuperation. The illness is produced by the fungus Ceratocystis ulmi, of a semi-parasitic character, transmitted by a bark beetle. Book Nr. 251, La leyenda del olmo pez (‘The Legend of the Fish Elm’), contains a bark piece of a great elm attacked by graphiosis, which disappeared near the train station of Cercedilla.

Another beetle, the Cerambyx cerdo or great Capricorn, is producing devastating damage in the oak groves south and west of the Iberian Peninsula. This oak groves are highly weakened by the drought and the bad pruning made in the past. It is very difficult to cure, because the big larva lives for two years inside the oak, drilling and pulverizing the wood and turning the oak very vulnerable to the growing drought and to strong winds, which break their trunks with enormous facility. I have seen the problem in the Alcudia Valley, Ciudad Real, and I have created some books where I symbolically protect the oaks, incrusting white quartz fragments from Monterrubio, La Serena, Badajoz, in the galleries devoured by the larvae (Book Nr. 830) or inserting transatlantic selenite pieces between barks (Book Nr. 995). In Book Nr. 954 there are Cúpulas sinfónicas de encinas (‘Symphonic Oak Cupolas’), collectors of menacing sounds, which navigated the banks of the Ganges and were deposited on the sand of the Marikarnika crematory in Veranesi. This musical spell is also related to the coded, secret language contained in the oak charcoal.

There are other endangered species. The Pinus insignis of Cantabria suffers the so called «pine cancer», caused by another fungus, the Fusarium circinatum, proceeding from the United States. But, in the end, the greatest enemy of the pines is the human being, and to defend them from him I drew defence lines with sulphur in Book Nr. 412. In much the same way I spread wale sperm among the beeches of Alkiza, Guipuzcoa, to contribute to their fertility and preservation in Book Nr. 923.

Salvations